Advertisement

A chart offers a wealth of clues for determining your position. Knowing how to use it may just prove useful someday.

Photo: Thinkstock

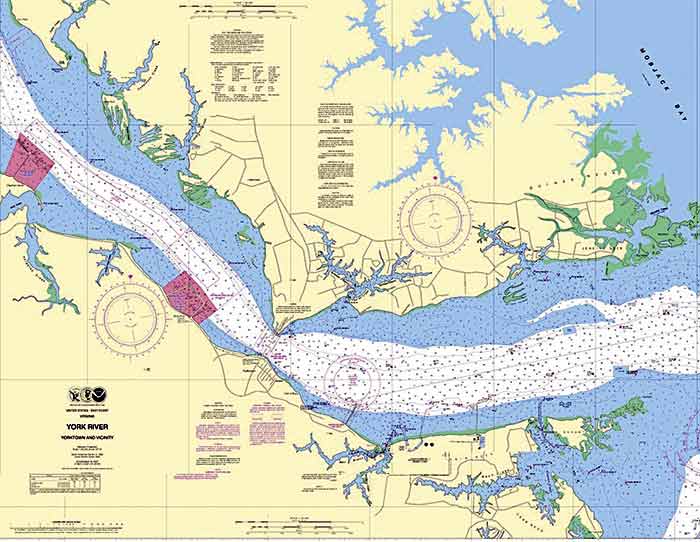

Even though GPS has revolutionized navigation, let's be careful not to let our navigational skills atrophy. Whether or not you have a GPS aboard, learning how to read the clues scattered across a chart is in your best interests. All you need are up-to-date charts covering your boating area, a compass (which you already have), and a ruler. Plus, paper charts are portable, can be drawn on, are viewable by the whole family at one time, and still work if you lose electricity or the GPS fails.

Landmarks

Start by getting everyone aboard into the habit of looking at the chart and comparing what they see along the coast with what's shown on the chart. Landmarks that can provide positional clues include a large bay, a peninsula jutting out into the water, the mouth of a river or creek, large smokestacks, and similar features that will be noted on the chart. You can make it into a game with the kids: "Who'll be first to find a tall, red lighthouse on a point of land sticking out into the water?" They can probably see those distant landmarks much better than you.

Next, have the winner find the landmark on the chart, then tell you what it's near or what it means about your location. Is it close to a favorite port, which may be around that point? You may need to explain some of the chart symbols, but it's fun to match what you see "for real" with chart symbols. Ask what the clue you see might mean regarding navigation. For example, is there a long shoal coming off the point or the mouth of your home river to the left of the point? With this game, you're not only finding what clues look like from charts; you're also building your own personal memory bank of what to look for to establish your location.

Tip

Coastal landmarks are not merely helpful; they can also be exciting and educational. For centuries, navigators recognized what we now call the British Virgin Islands when they saw the "fat virgin." Virgin Gorda, in translation, was reportedly named by Columbus when he first saw the island's distinctive profile on the horizon. The shadowy Grey Lady rising from the sea long ago helped returning whalers know they were closing with Nantucket. Point Conception's distinctive bluff headland marks the natural division between Central and Southern California and is believed by the Chumash people to be the Western Gate through which the souls of the dead pass. The spindly Stingray Point Light indicates where Captain John Smith, who'd been stung while spearing fish with his sword, lay on the sand, directing his men to dig his grave so that he could spend eternity looking out over the Chesapeake. You can learn about these and countless other landmarks from good guidebooks, which are also important to keep aboard. Fort Lauderdale's Bluewater Books and Charts can provide online or phone advice about guidebooks.

Aids To Navigation

Aids to Navigation could be considered the man-made "landmarks" of the water. They are designed to be identified from a distance, and the colors, shapes, markings, lights, and sounds of the various aids provide key navigational information. Aids to Navigation include, among other things, lighthouses, nun and can buoys, and daymarks; each type has its own symbol on charts. Once you can recognize the various Aids to Navigation, you'll be able to identify a specific one (by color, number or letter, light-flash pattern, or sound) and match it up to the chart. If you're positioned next to a navigational aid, then you know exactly where you are on the chart.

Again, your kids will probably be much better at picking out the next buoy and identifying it when the number on it is still too far away for your eyes to read. Most crowded boating areas have dozens of Aids to Navigation, and it's possible to navigate successfully from one to another without using a GPS at all. When you and your family get comfortable matching the aids on the chart to what you see on the water, try spending an hour with the GPS off using only navigational aids and landmarks to find your position.

Seamarks

Clues to your location aren't only found above the water. Learn underwater clues as well. Your depth finder should tell you the depth of water where you are. The chart will also tell you depths and their location. You may run across a sudden rise in the bottom, then a decline. Your chart may show this and its location relative to the shore. A sophisticated depth finder can distinguish between a rocky and a soft mud bottom, or even a bottom with tall sea grass. The chart may tell you where that is. The bottom off a river may have a broad, shallow, submerged delta or a deep cut channel. If you see this on your depth finder and also on the chart, you may know where you are. The chartplotter should also give you this information, if you have it configured to that level of detail — and you should. But if you're already accustomed to noticing these shifts in bottom contour on the paper chart and matching them to the depth finder as you cross over them, you'll be better able to find your way, or at least know where you are, if the chartplotter quits.

Advertisement

Dead Reckoning

Pirates never used chartplotters, and their depth finders were lead lines. But they found their way. Take a lesson from them. Bring along a ruler to use with your chart. Using the chartplotter or a GPS position from a cellphone, plot your position on the paper chart as you go along. To plot your course on paper, simply take the latitude and longitude coordinates from the GPS. Find the corresponding coordinates on the edges of the chart. Typically, the longitude coordinates are on the top and bottom edges, and latitude coordinates are on the left and right edges; some chart books have chart views arranged at other angles for space or clarity purposes. Using a straightedge, make a light pencil mark where the lines intersect. For a better, more versatile tool, get a Weems & Plath No. 104 Protractor Triangle (about $20).

After you've plotted three or four positions, wait 15 minutes or so, then turn off the chartplotter, paying close attention to the compass heading as you do so. Now try to keep track of your position without it. You may not know where you are at that moment, but you'll know where you were 15 minutes ago, and that'll be a pretty good clue. If you know this, you can "dead reckon," which comes from the phrase "deduced reckoning" and means steering by your compass while taking note of your speed and passing time to determine distance traveled. You'll likely find your way to where you want to go, or at least be close. You can also use landmarks, seamarks, and Aids to Navigation to verify and adjust your dead-reckoning position.

Unlocking the navigational clues scattered across your chart won't only add to your onboard fun — it will keep you safer should something knock out your electronics.

No Land In Sight? Let Nature Help You Navigate

- Notice the clouds. As the cool sea breeze floods over the hot earth on summer afternoons, high cumulous clouds form over land, and these can be seen from offshore.

- To determine direction and intensity of current, in clear water look for movement of grasses and soft coral.

- Large bodies of water, such as the Gulf Stream, that are warmer or colder than surrounding water create different clouds above them.

- Shallow clear water, because of its bluish tint, often reflects on the underside of white clouds.

- Plumes of smoke may indicate power plants or facilities too far away to see.

- In the fall and spring, flocks of migrating birds can indicate general north or south directions. In the morning or evening, such flocks might be heading away from or toward a nighttime layover destination on land.

- Small land birds seeking refuge on your boat far from shore usually take off in the direction of land after resting.

- Sun rises in the east, sets in the west.

- Know the direction of the prevailing sea breeze, which usually cranks up in the afternoon.

- Often you can smell land: marshes, exposed mud at low tide, seaweed on rocks, or particular industries that are common in port towns, such as paper mills and fertilizer plants.

- If weeds/grasses float by, land may be near. A trail of debris means you may be off a river that flows past a city.

- Short, tall waves that seem out of context may indicate a current flooding out of a creek or river into the wind.

- An upwelling or eddy may indicate a shoal or similar bottom contour.

- Seagulls walking instead of floating give you a clue as to where you don't want to be.

Where To Get Your Paper Charts

NOAA announced in October 2013 that the government was getting out of the printing business. For the first time in 150 years, it no longer will print traditional large-scale paper charts. But that doesn't mean there aren't other options. You can purchase printed charts through private companies. You can also go to nauticalcharts.noaa.gov to download for free a full chart in printable booklet form; if you just want a small section, view charts for free at charts.noaa.gov and print a simple chart view of your choice. Even in a small boat or PWC, you can keep paper charts safe in a large resealable plastic bag.